The Mystery of Street Signs in Buildings

New York’s soul is young. Even though many of us live in century-old buildings, we don’t spend much time thinking about how our spaces were built to fit the mundane details of other people’s – 19th-century people’s – lives.

For years, I’ve been fascinated by street signs embedded in Brooklyn buildings. It’s a window into a past where architects and developers felt a need to literally carve street names into their buildings. I want to know why. Was it civic duty or a mandate?

Embellished examples like these indicate that this probably wasn’t always cheap.

7th Ave and 13th St in Park Slope

22nd St and 5th Ave in Park Slope.

These street signs contributed to some common good, perhaps helping newcomers and passersby get their bearings – because one of those mundane details is that there weren’t modern street signs like the ones we take for granted.

Here’s a map of the examples I’ve found in Brooklyn. It’s not exhaustive, obviously.

Many of these signs are on the second or third story. But not this example at Willoughby and Lewis in Bed Stuy, just a few feet off the ground. Are those transportation methods might be a clue here? Neither Willoughby or Lewis had either a trolley or an elevated train.

Willoughby Ave and Lewis Ave in Bed Stuy

St. Johns Pl, Washington Ave, Greene Ave, Seventh Ave and Bedford Ave all had trolleys (that have since been replaced with buses along similar routes).

Fulton St and Fifth Ave each had now-long-gone elevated train lines, while the Long Island Rail Road once ran on ground level on Atlantic Ave. (Now it’s in a tunnel underneath some sections and elevated above others.) In old photos, billboards adorned the buildings next to the els.

Builders could have had el riders in mind when they built signs a story or two up, where passengers could see them – as you can today if you were leaving the Myrtle Ave. station on the J/Z trains.

Broadway and Stuyvesant Ave. in Bed-Stuy

Of course, there’s another possible explanation for why they’re so high: eye-level space on a corner is valuable, so architects either didn’t put street signs there often, or the ones that were there have since been covered up or taken down.

Corner lots seem to be frequently torn down and rebuilt – they’re prime real estate – so I’d guess that many street signs have disappeared. Many buildings have been covered in vinyl siding or commercial signs.

But these simple signs bring us back to the mystery: What attenuated sense of civic duty impelled a developer to enlist a mason to carve these relatively-barebones versions? This custom stonework must have been more expensive than a even a handpainted sign.

Atlantic Ave and Grand Ave in Prospect Heights

Fulton St and Grand Ave in Clinton Hill

Classon Ave and Greene St, in Bed Stuy

Classon Ave and St. John's Pl. in (hahaha) ProCro

Precisely dating the stonework streetsigns is difficult. As far as I know, no database of building construction dates exists that is accurate into the 1800s.

Fire insurance maps can give an idea of when a building first appeared at a site, but since some lots have hosted two, three or more buildings since Brooklyn morphed from farmland to a city, it’s hard to be sure.

Changes in street names can be useful, though they’re imprecise. I’ve found two signs (which I wrote about last year last year) on St. Marks Ave that still read Wyckoff Ave – which was renamed between 1869 and 1874, based on fire insurance maps.

Many of the extant signs are barely legible now – though lasting more than 100 years is no mean feat.

14th St and 7th Ave in Park Slope

Bedford Ave and Monroe St in Bed-Stuy

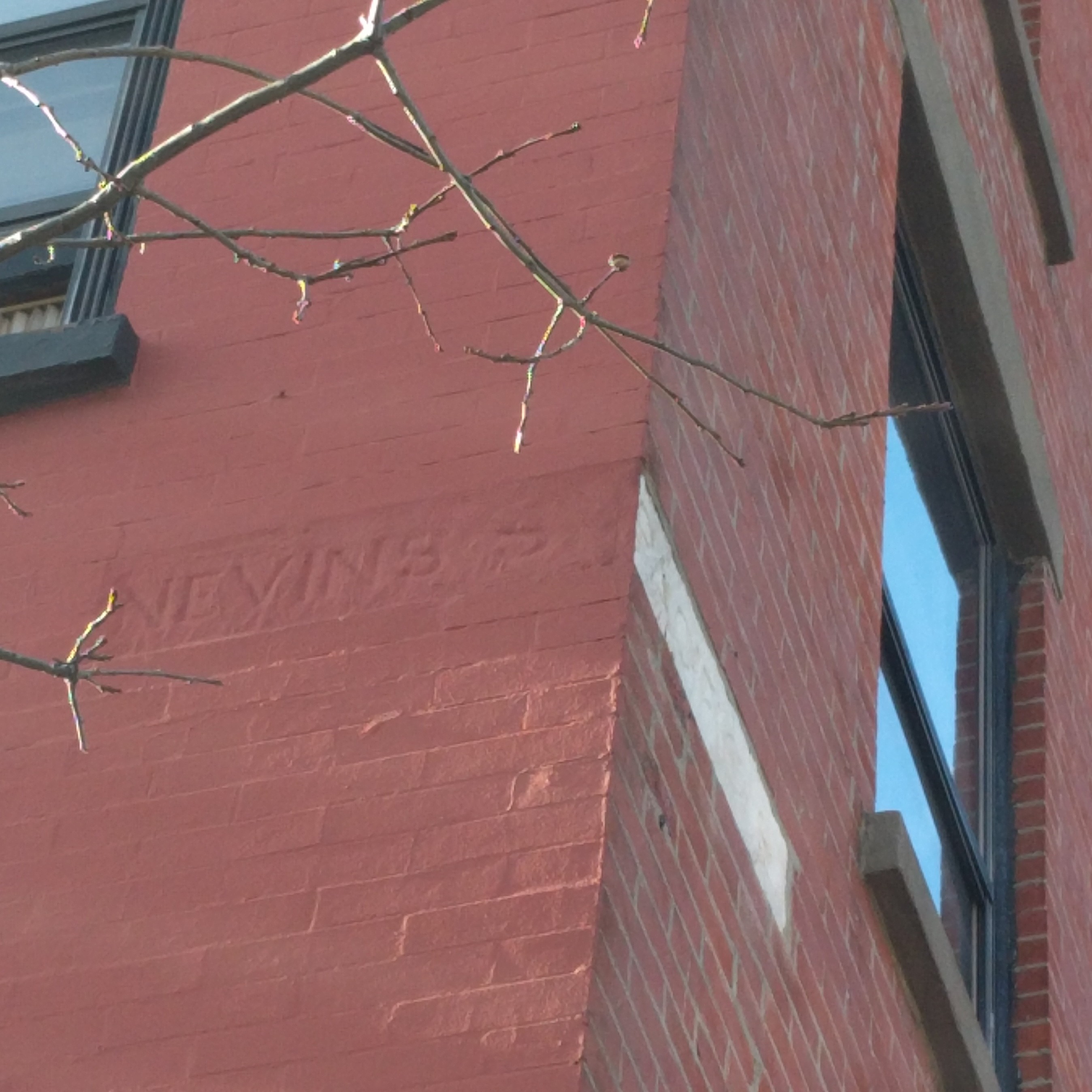

Nevins St and Pacific St in Cobble Hill

These enamel street signs are fairly common and seem standardized. Based on the design, I’d guess they’re newer, that is, that they’re an intermediate evolutionary phase between carved stone and today’s familiar pole-mounted signs.

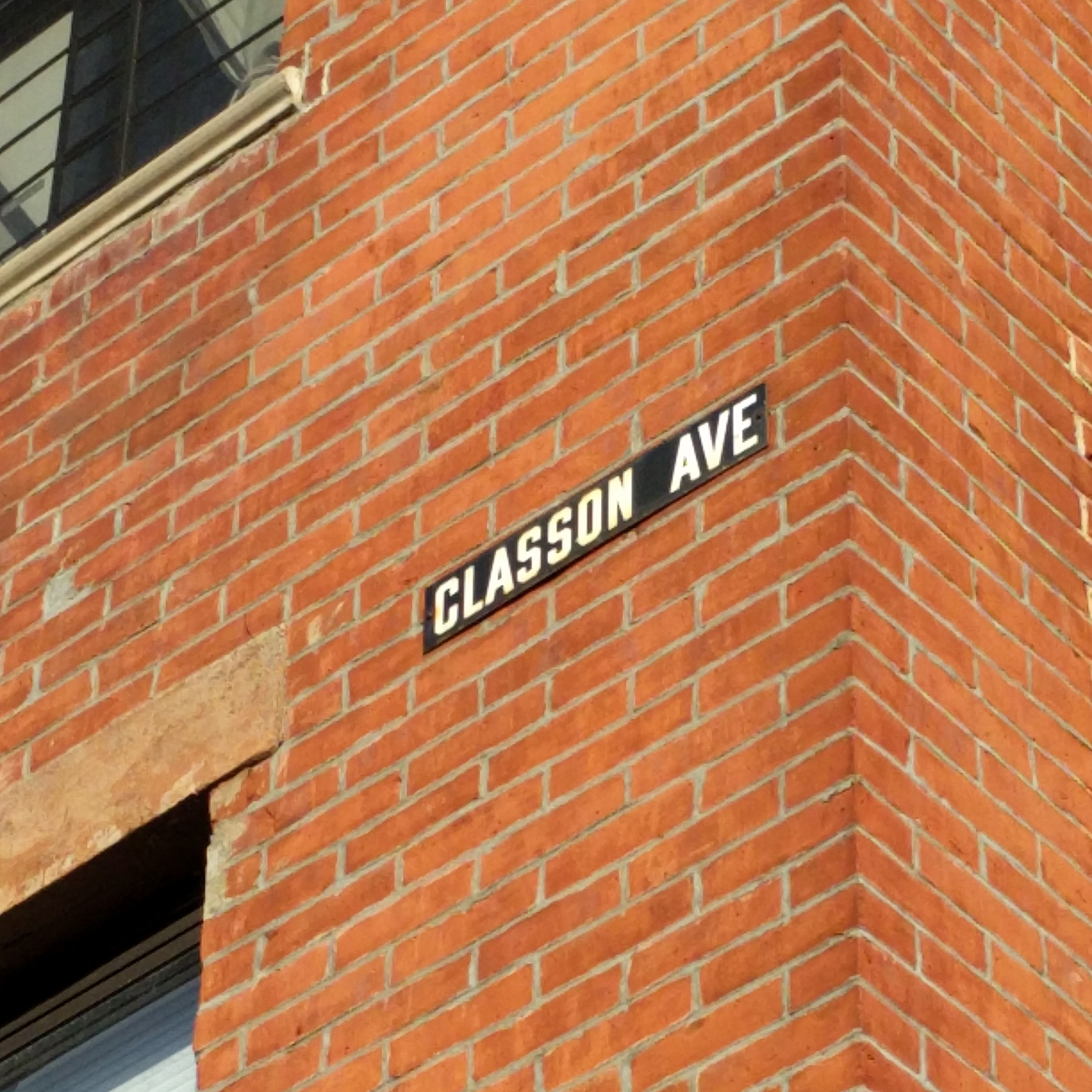

Classon Ave and Greene Ave in Bed Stuy

Washington Ave and Park Place in Prospect Heights

Pacific St and Court St in Cobble Hill

Smith St and Pacific St in Cobble Hill

Sumner Ave, on this pair of enamel streetsigns, is mounted on the castle-like Sumner Armory at the corner of Jefferson Ave and Marcus Garvey Boulevard in Bed Stuy. The street was renamed to honor Garvey in 1987 (after a brief period as “Marcus Garvey Ave”).

Jefferson Ave and Marcus Garvey Blvd (formerly Sumner Ave)

I wonder when city government, whether New York or, pre-unification, the City of Brooklyn, began putting up modern street signs – and when that became a duty of the government.

The inconsistent stonework street signs definitely wouldn’t work in today’s world: they’re far too hard to see at 25 miles an hour. Standardized street signs are probably easier on drivers, and they being appearing in photographs from OldNYC in the 1930s or early 1940s.

Vanderbilt Ave and (unlabeled) Dean St in Prospect Heights

Flatbush Ave and (perhaps covered up?) Bergen St in Park Slope

Besides these streetsigns, another example of how historic norms shaped our city – one that’s often cited and which I haven’t fact-checked – is property taxes that were levied per floor of a building. Supposedly, New York city architects put dormer windows in attic spaces so that they wouldn’t be counted as a floor by tax authorities.

Even today, new apartment buildings are often built as several identical, but technically-separate, buildings, which lets them avoid complying with zoning rules that require larger developments to include parking.

At some point, I’d love to research if there were similar legal sticks or carrots to influence builders to install these street signs.