That Plane Overhead: Starring Our Friends SDR, ADS-B, I2C and KLGA

You may ask yourself, “How did I get here?” - Talking Heads

I have a constant reminder of how I got here. In late May 2012, I flew to LaGuardia Airport to start my career in New York City. Every day, especially when it’s cloudy, airplanes descending into LaGuardia fly directly over my apartment. Sometimes I wonder who’s moving to New York, hoping to make it beneath the lights of Broadway, but I know most folks are just coming for a meeting.

So instead, I just wonder where they’re coming from.

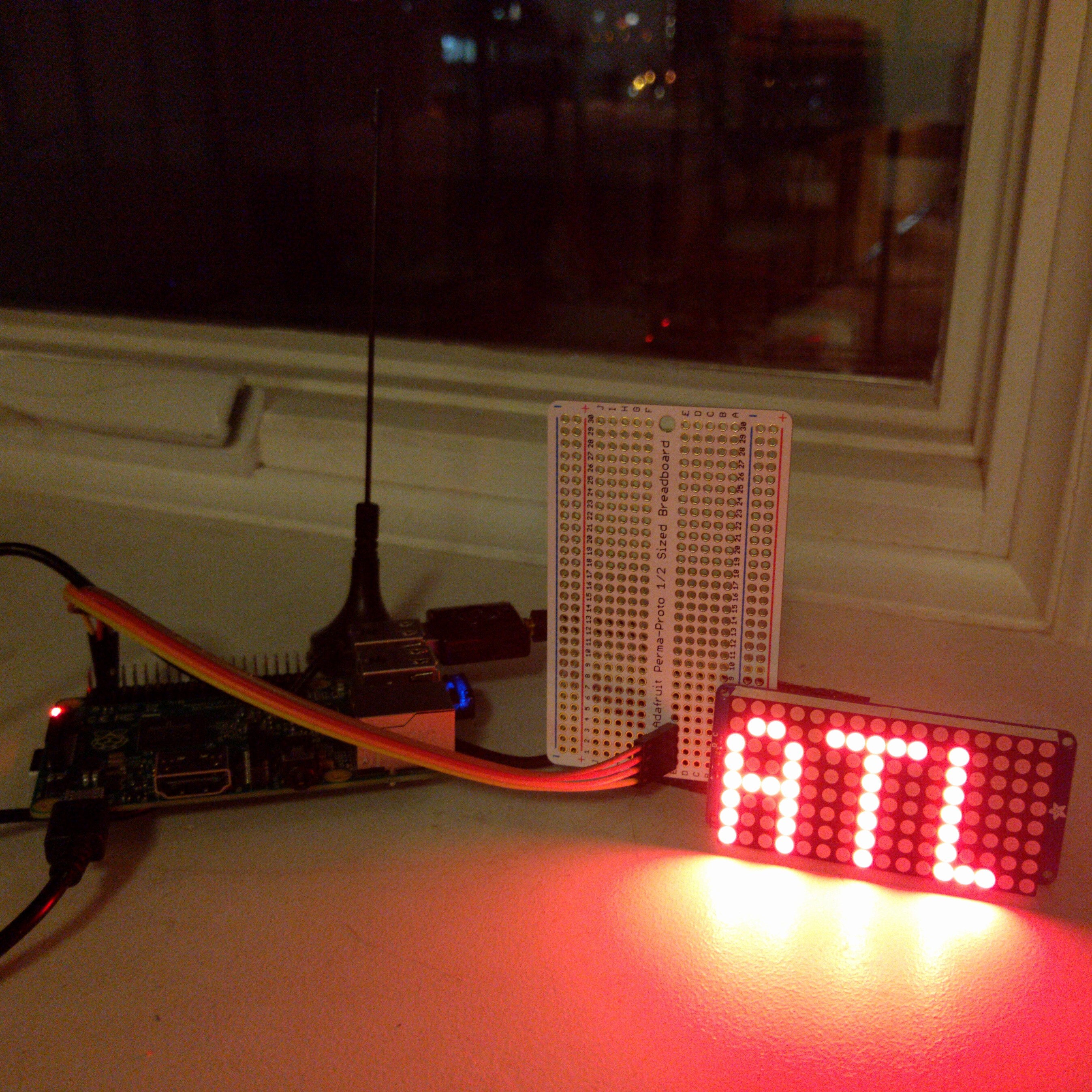

I built a little display in my living room to tell me.

This contraption uses a Raspberry Pi and a Software-Defined Radio antenna, along with some neat software and databases, to display on a 16x8 LED display the departure airport of the airplane that’s flying overhead. The software that runs it, which I’ve dubbed Flyover, is open-source.

So how does this work? Let’s start from the beginning.

Passenger jets reportedly collect one terabyte of data about themselves per flight. Of that terabyte, most airliners broadcast a tiny portion, unecrypted, over the air, via radio systems called ADS-B and Mode S. Every few seconds, they announce their location, altitude, registration number and – usually – the flight number.

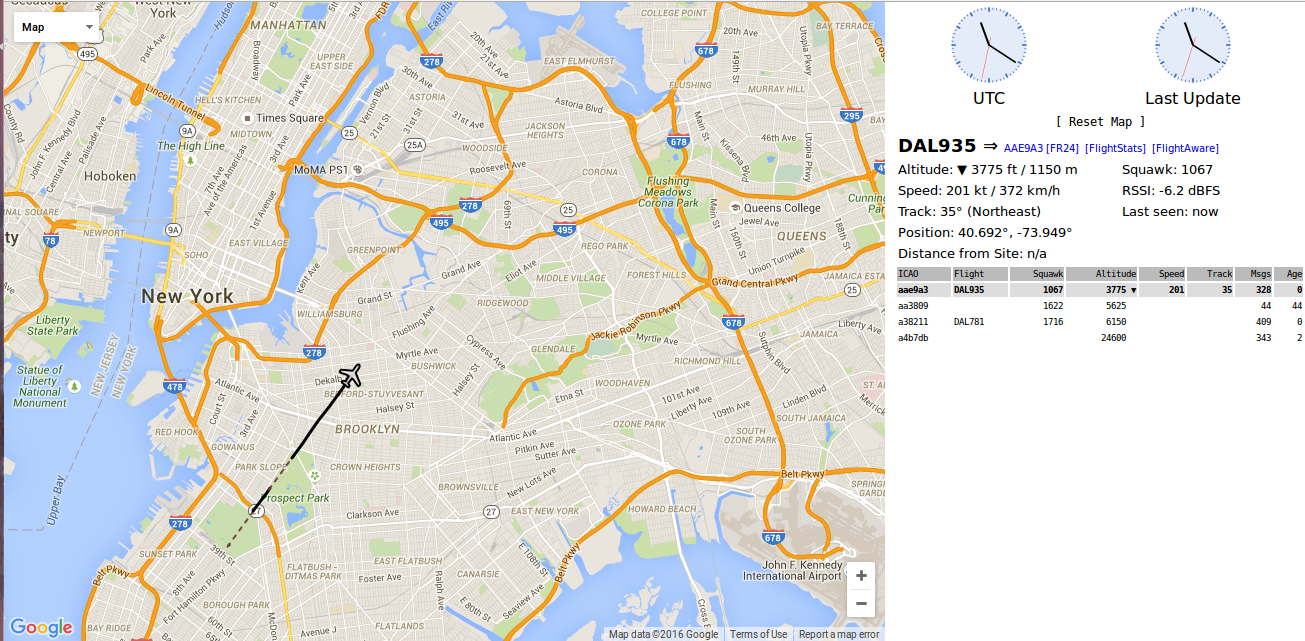

Dump1090 is a program that listens to those broadcasts. Its web interface shows each plane’s precise location and path. I can pick up just about any plane within line of sight of my north-facing window in Prospect Heights. I can “see” planes well into Connecticut or Rockland County, but if the plane shows up even over Prospect Park, I often can’t detect it.

But I don’t want a map on the web. I want a display on my windowsill.

We extract the data on each plane from Dump1090’s JSON feeds, the ones that feed that map. So, we have an always-up-to-date JSON feed of airplanes by their flight number.

But which one to display? New York’s airspace is crowded. Cops, rich dudes and sightseers fly around in their helicopters; we have three major airports nearby. The nearest airplane to my apartment is usually the LaGuardia-bound one, but sometimes a transatlantic flight, or maybe one headed north to Boston, flies over, at a much higher altitude. We have to exclude those. I’ve eyeballed the rough corridor that flights to LaGuardia arrive in and exclude anything outside of there; I also exclude anything higher than 10,000 feet. If it matches those heuristics, the plane is the one I’m curious about.

With that plane’s flight number, we can figure out what route it flies. Virtual Radar Server compiles – and offers, free – a database of routes. It’s not always right, but it’s pretty close, and frequently updated. Suppose the flight number is DAL935 (that is, Delta Air Lines flight 935). We get the route, in the format of “KMCO-KLGA”, since it’s a flight from Orlando, but have to figure out which airport to display.

Sometimes a flight number is only used for, for instance, a once-daily flight from Orlando to LaGuardia. That’s easy – display Orlando’s airport code, MCO (lopping off the K from KMCO; the K just means it’s an airport in the United States). Sometimes, it’s a little harder, because some airlines designate several segments with the same flight number: maybe a flight from Orlando, to LaGuardia, then to Chicago. In that case, if the plane is descending, display Orlando; if it’s ascending, then Chicago.

Once we have the airport code, we display it. The nitty-gritty of how to set up and write to an I2C board like this is complicated – I had to solder for the first time in a decade AND I had to modify the library to write to a 16x8 board – but Adafruit’s tutorials and libraries make it a lot simpler. Once the display library is set up, I tell it the airport code (e.g. MCO) and it handles everything else. I can even pick the font and could make the text scroll.

The scripts run on a cron, twice a minute. The display itself takes pride of place on the windowsill – another source of “ambient notifications”, but a little less actionable than my bus tracker.

Want to build this project yourself? Here are instructions.

Postscript _January 27, 2016_: A lot of you folks are interested in this project! I’m flattered, I really am. I’ll make a note here of the fact that my project was written about by Mashable and Yahoo Travel.